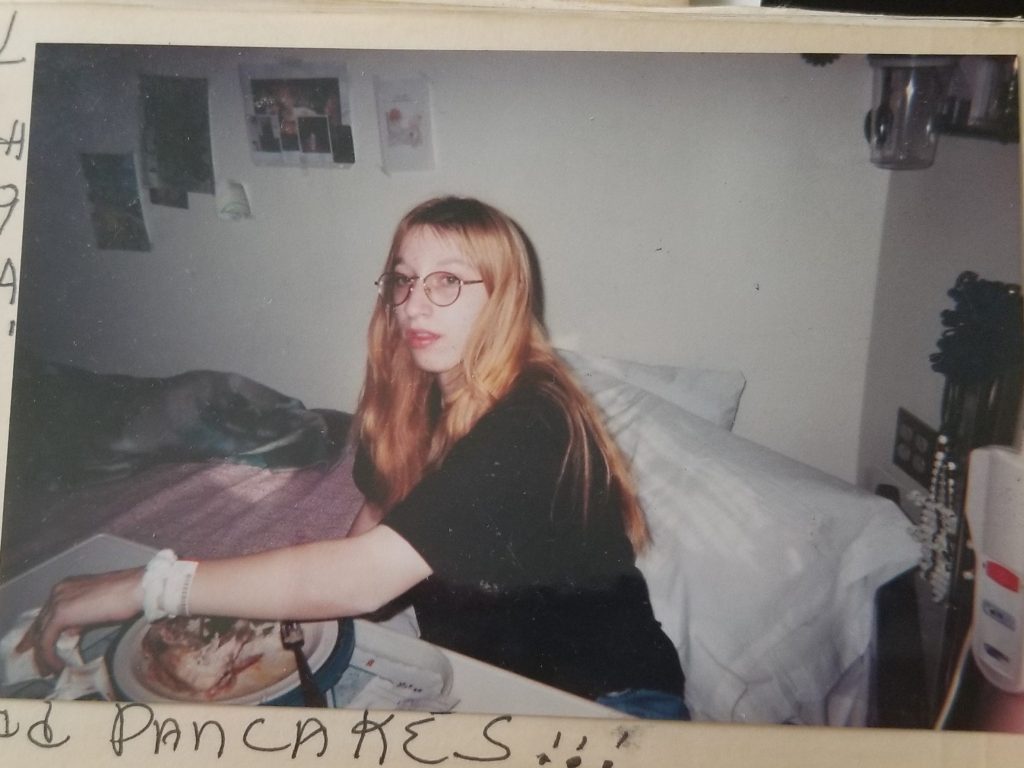

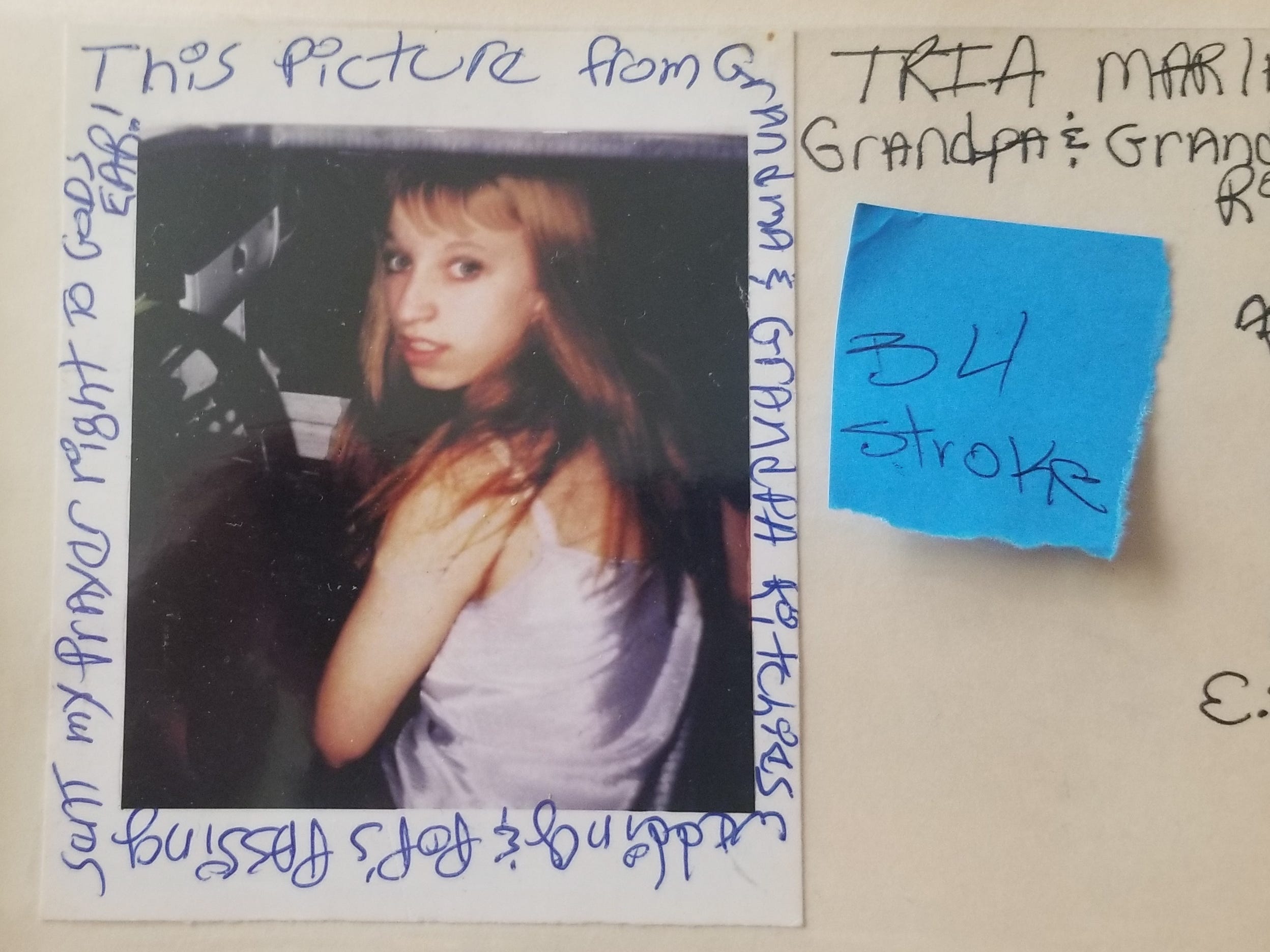

Tria Potts

- Tria Potts had a stroke after going on birth control at age 15. Doctors thought it was drugs.

- She was in rehab for five months, but still became the first in her family to graduate high school.

- Potts had a severe blood clot while pregnant at 25, but was turned away at the first hospital.

- Visit Insider's homepage for more stories.

Tria Potts doesn't remember losing consciousness at age 15 while her eyes rolled toward the back of her head. Her grandmother told her about that.

Her memories of coming-to in a hospital bed after 27 days in a coma are fuzzy too. Her mom told her her first words were "Michael Jordan" before she reverted to using sign language, which the straight-A student been studying. Speaking, like eating and walking, would be something she'd have to relearn.

Potts, now a 37-year-old mom of two in Battle Ground, Washington, had suffered a massive stroke, something one doctor later attributed to her birth control pills. She also knows now she has a genetic predisposition toward blood clots. But the only explanation that seemed to make sense to clinicians at the time was illegal drugs.

"The doctors swore to my mom that I had overdosed on drugs or done some experimental thing because it was so uncommon for a 15-year-old just to have a stroke out of nowhere," Potts told Insider.

While Potts' experience happened decades ago, experts and other women have told Insider the challenge of having life-threatening condition taken seriously as a young woman persists.

Potts went on birth control to manage painful periods

Potts went on Ortho Tri-Cyclen, a combination birth control pill containing estrogen and progestin, at age 15 to manage periods heavy and painful enough to keep her home from school. "The doctor assured me that it's 1 in a million chance that I would have a stroke or any side effects," she said.

So she and her mom decided to accept the prescription without requesting blood tests. "That was our biggest mistake," Potts said. Less than a month later, she had a stroke. It was caused by multiple clots, at least one which traveled from her heart to the brain.

Tria Potts

Doctors had to drill a hole in her head, Potts said, to relieve the pressure. (Much to her disgust, her aunt and uncle still have the drill to commemorate one of their scariest times of their lives. Fortunately, Potts said, "it's clean and stuff.")

Potts was in a coma for 27 days, during which doctors conducted "every test possible test," she said. They found that she had protein S deficiency, or a disorder that increases the risk of abnormal blood clots. Potts also learned she naturally produces a lot of estrogen, another clot-risk booster. Adding combination birth control seemed to light the fire.

And yet, no one put that together until the day of Potts' release from rehab, when a doctor told her and her mom he was sure the pill triggered the stroke.

Birth control raises the risks of clots, but it's still less than a one in 1,000 chance

Estrogen, a hormone found in combination hormonal-birth-control methods, increases the risk of any type of blood clot. That's because it prompts the body to produce more of the plasma that helps blood stick together. Older iterations of birth-control pills tended to contain higher levels of estrogen, making clots more likely.

These days, the risk of birth-control-linked clots can generally be compared to rare but serious events like a car crash, Dr. Melanie Davies, a gynecologist in London and professor at University College London, previously told Insider.

"For 10,000 women over a year, one to five will have a blood clot anyway, and on the [pill] that rises to three to nine, so it is still less than one in 1,000 chance," she said.

Rare doesn't mean worth dismissing, though. In interviews with 24 women who'd had negative birth control side effects, including clots from pills containing drospirenone and ethinyl estradiol, researcher Alina Geampana found women didn't think they'd received enough information about the risks before starting the pills.

"It's one of these things where if this was a man's issue, this would have been solved like a hundred years ago," Rebecca Ungarino, an Insider reporter who had a birth-control-linked stroke at age 20, said in a previous story. "That's how I feel, like no one would be getting blood clots. It's just crazy to me."

Potts spent five months in rehab and almost dropped out of school

When Potts finally woke up on day 27 for no apparent reason, her mom wasn't surprised. "My mom [had] said, 'There's no way in hell she's not going to wake up.' I'm too pig-headed," Potts said.

That attitude humbled her during inpatient rehab, too, where she spend five months in speech and physical therapies.

"I remember trying to walk and do things on my own and then realizing, OK no, I can't and I need help," Potts said. "And it was embarrassing."

Tria Potts

Returning to school was maddening, too. "My train of thought was all over the place," she remembers. "I'd read a sentence or two and lose my spot and get so upset with myself that I'd break out crying. Then I'd have to excuse myself."

She almost dropped out to get her GED, but remained steadfast in her goal to graduate - even though she needed to do summer school to catch up. She graduated with her class in 2002.

Potts had deep vein thrombosis during her pregnancy

After high school, Potts used a progesterone-only birth control pill and saw a doctor every six months. "For quite a few years, I was a normal person."

Then, she got pregnant. Blood clots are more common in pregnancy and the three months postpartum than on birth control, even for people with no history. As many as 65 out of every 10,000 new mothers experience a clot. Potts ended up being one of them.

She was working the night shift at a casino when the pain in her leg was so debilitating she couldn't stand.

Her dad, who also worked there, drove her to the nearest hospital. There, she was told the pain was happening because of the way her daughter was positioned, and she was released. Potts knew they were wrong. So she went to another, bigger hospital, where she'd been receiving prenatal care, and made her case.

An ultrasound quickly revealed Potts had a clot that extended from her groin to her kneecap, diagnosed as deep vein thrombosis. Potts was promptly treated with a heparin drip, and had a healthy baby two months later.

"If I don't get some kind of answer or a second opinion, I go somewhere else," she said. "I feel that we know our bodies better than doctors."

Tria Potts

These days, Potts' biggest lingering side effect from her stroke is poor short-term memory. She also says her smile isn't quite symmetrical, but no one else notices. She's been on Warfarin for 22 years and had a hysterectomy to reduce her risk of ovarian cancer; she has the BRCA gene. That took care of her heavy periods, too.

Her biggest gripe is that, when she tells people, doctors included, she had a stroke at age 15, they say, "Oh no, you didn't," Potts said.

In medicine, combinations like "young people" and "strokes" often doesn't compute. Brittany Scheier, a lawyer who had a stroke a few years ago at age 27, also told Insider about how her symptoms were brushed off in the ER as drug- or alcohol-related.

Dr. Suzanne Steinbaum, an American Heart Association Go Red for Women volunteer medical expert and cardiologist in New York City, previously told Insider it remains critical for women - who are more likely to get, and die from, strokes than men - to advocate for themselves.

"So many times I hear, 'I was listening to the doctor. Maybe they're right,'" she said. "No one knows our bodies as well as we do. Nobody is living in our bodies. We know when we're not OK."